The annual Festival de Cannes is in full swing. As usual, in the official selection, we can see everything from directorial debuts (for example, the coming-of-age drama “Wild Diamond” by Agathe Riedinger) to loud comebacks (like “Megalopolis” by Francis Ford Coppola, his longtime passion project). The range and variety of films presented at the festival bring us back to the topic of the filmmaker’s voice. We tell stories differently and that’s what keeps the motion picture’s heart beating. How can you develop your voice and what does the term “narrative perspective” have to do with it? Let’s find out!

Every director has a different signature (which can change from one work to another). We see it in lens preferences, defined camera movements, lighting approach, and much more. However, as seasoned filmmaker and educator Tal Lazar points out in his MZed course “Cinematography for Directors”: most if not all of these visual choices are connected to narrative perspective. What does it mean, though? Below, we peek into some of Tal’s lessons that not only define this term but also explain how to use narrative perspective as your own wizard’s wand. Some exciting film examples are also waiting ahead!

Head over here to watch the entire course.

What is the narrative perspective?

Stories always have someone who tells them – the so-called narrator. From classic literature, we know that there are different narrative modes. Either the main characters show us around themselves (and then we get the “I woke up at dawn” type of lines), or the story is told from the third person perspective (“She woke up at dawn”). The latter is divided into “restricted” (when the narrator stays objective and cannot get into the character’s head) and “subjective” (someone like the all-knowing god). The question is: can we also use these narrative modes in movies? Tal Lazar explains that yes, we can, but not always in the literal sense.

This is a point-of-view shot from “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde”, where we see everything through the protagonist’s eyes. It can’t get any closer to the story, written from a first-person perspective, can it? Well, it doesn’t necessarily work this way. As Tal Lazar emphasizes, to make a narration feel subjective, the viewers should be able to access the character’s thoughts and feelings, which is rather difficult when you don’t see the actor’s face. There are other tricks to achieve it, and we’ll talk about them in a moment.

Objective and subjective

But first, let’s draw the line between objective and subjective narrative perspectives.

As already mentioned, subjectivity allows us – filmmakers – to express the inner voice of the character. Using it, the audience immerse themselves in their experience, feel what they’re feeling, and emotionally connect. What’s exciting is that we don’t need any words for that. In numerous cases, the reaction shots will tell you much more than the action or dialogue.

Objectivity, on the other hand, lets the viewers observe the characters from afar and communicates the context. Sometimes, it means we get to know an important bit of the story the characters are unaware of. Do you remember the legendary opening scene from “Touch of Evil” with the bomb in the trunk? That’s a perfect example of using an objective narrative perspective in a powerful way:

At the same time, an objective perspective allows the audience to disconnect and judge what the character is doing and why (which may be difficult, if you feel too involved with the character’s view of the world). Tal Lazar offers the example from “Birth” – a bathroom scene that created a massive discussion because it felt really uncomfortable to a lot of people:

How does this film still make you feel? A wide shot, where we don’t see Nicole Kidman’s face, and a child, who claims to be her reborn husband, both nude in the same bathtub. We’re removed from their emotions and start developing our own judgment of the situation, which is indeed uncomfortable to witness. Was this the impact the director was going for? Very likely.

A wisely chosen narrative perspective is one of the most important directorial decisions to make, and an effective tool that can really form your voice. Every filmmaker will approach it differently, but to do so, we should first understand how to use it in general.

Different techniques to control narrative perspective

There is a great variety of different techniques to control narrative perspective and promote either an objective or subjective one. Most of them are closely connected to visual storytelling tools we often write about here (you can read our articles on camera language, visual subtext, or aspect ratio, for example).

Among others, Tal Lazar emphasizes the following techniques that are imperative to learn and understand if you want to create “effective” shots:

- Camera position and its placement within the scene. Where should it be? Far away or close? In front of the actor, to the side, or behind them? Below or above eye level? These are the very first decisions that will be affected by your choice of narrative perspective.

- The distance from the camera to the subject. When we watch the character from afar, we concentrate more on the context. On the other hand, when the camera is close to the face, we get access to a person’s thoughts and feelings.

- Lens choice, which works hand in hand with the camera distance. Thus, a wide-angle lens placed closer to the character will make us feel physically nearer to them as opposed to a long lens (the subsequent images below demonstrate this effect).

- Using foreground as a divider between the audience and the character. Imagine you see the protagonist through the window. How will it make you feel? Visual obstacles usually remind the audience they are not in the same space as the characters. They watch the events rather than experiencing them.

- Camera movement: motivated versus unmotivated. Both can be used for objectivity or subjectivity, depending on how and when we trigger the motion.

Multiple narrative perspectives

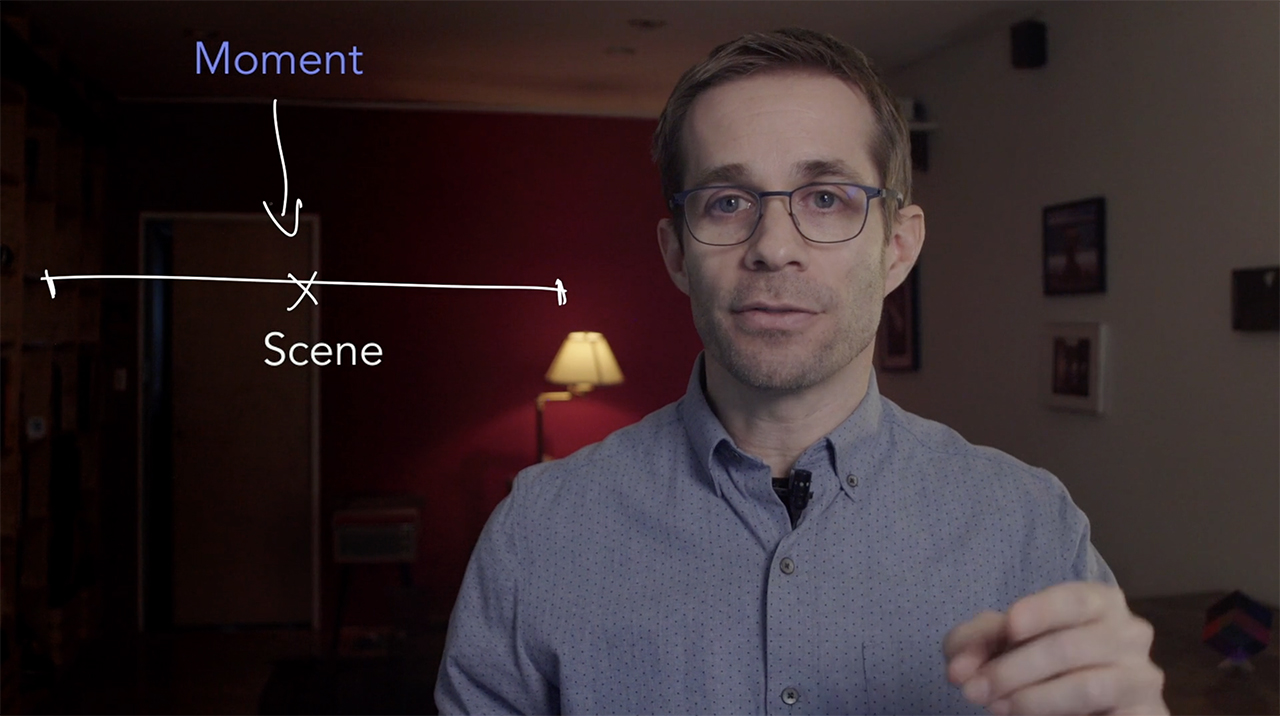

Narrative perspective might change mid-shot. Moreover, you can use multiple ones if you have more than one character (with a story to tell) in the same scene. Tal Lazar shows this phenomenon in the example from the movie “Road to Perdition”. Let’s rewatch together the following scene (from 02:33), where Michael Jr. comes to his father after a bad dream and they talk.

What story elements and visual choices have you noticed? How do they work with each other? Let’s start with the protagonist Michael Sullivan. He tries to connect to his son – possibly for the first time ever. The whole intimacy of this situation doesn’t come easy to him. As Tal Lazar points out, we can see the exact moment when he uses the opportunity to talk (after Michael Jr. admits that he also hates math). The filmmaker emphasizes his decision with the first close-up of Tom Hanks’s face:

Michael Jr. also takes a meaningful step in this scene. He asks his father why he treated him differently than his deceased brother. Here, we see a similar technique – again, jumping in the editing to a close-up.

Please note that these close-ups wouldn’t work this way if the scene consisted only of them. To make the chosen moments mean something, editors had to gradually build up to them using other shot sizes before and after.

Another interesting aspect Tal Lazar draws attention to is when exactly the cuts take place. Filmmakers don’t jump closer to the characters during their dialogue lines but before them. They are interested in internal processes much more than in what both father and son have to say. That’s how the camera shows us “between the lines”, taking on a subjective narrative perspective.

Planning narrative perspective to tell engaging stories

Of course, editors wouldn’t be able to use this technique if they didn’t have the necessary footage. That’s where the preproduction collaboration between the director and DP plays an important role. If you know the story and have defined the narrative perspective for all parts of the scene, you’ll be able to approach your shot list differently. Tal Lazar recommends doing it not chronologically, but starting with a particular moment. What is it you want to emphasize? What is the essence of the scene?

You can emphasize a moment by making it different from others (visually, sonically, rhythmically, etc). So, start from it and think of the technique that will support this particular story element at its best. Then, you’ll be able to block the rest of the scene around it. The knowledge of narrative perspective can also be of immense help during the shoot. This way, you won’t forget to capture the essence when the shooting time suddenly runs out

According to Tal Lazar, filmmakers starting out often lean towards an objective perspective. They are afraid people won’t understand their films so they try to include as much context as possible. Film schools also teach us to begin a scene with an establishing shot – usually a very objective demonstration of the space. But does it always help to deliver your initial idea? I doubt it.

I always tell my students to stop trying to make movies everyone understands but no one feels. Instead, try to make movies that are confusing, but everyone feels.

Tal Lazar

After all, your audience might be smarter than you think.

If you want to gain more insight into the filmmaker’s voice, narrative perspective, and visual tools at your disposal, head over to MZed.com and watch the “Cinematography for Directors” course.

What else do you get with MZed Pro?

As an MZed Pro member, you have access to over 500 hours of filmmaking education. Plus, we’re constantly adding more courses (several are in production right now).

For just $30/month (billed annually at $349), here’s what you’ll get:

- 55+ courses, over 850+ high-quality lessons, spanning over 500 hours of learning.

- Highly produced courses from educators who have decades of experience and awards, including a Pulitzer Prize and an Academy Award.

- Unlimited access to stream all content during the 12 months.

- Offline download and viewing with the MZed iOS app.

- Discounts to ARRI Academy online courses, exclusively on MZed.

- Most of our courses provide an industry-recognized certificate upon completion.

- Purchasing the courses outright would cost over $9,500.

- Course topics include cinematography, directing, lighting, cameras and lenses, producing, indie filmmaking, writing, editing, color grading, audio, time-lapse, pitch decks, and more.

- 7-day money-back guarantee if you decide it’s not for you.

Full disclosure: MZed is owned by CineD.

Join MZed Pro now and start watching today!

Feature image source: film stills from “Road to Perdition” by Sam Mendes (2002).

Do you think about narrative perspective in your movies? Can you name any films or directors who stand out in terms of using it? Please, share your insights with us in the comments below.